Basic Income and Green Economics

How a Recession could be Fun

This weblog ‘Page’ is based on a résumé of Citizens’ Income and Green Economics published by The Green Economics Institute greeneconomicsinstitute@yahoo.com

My ‘Page’ Resume as a Springboard is the basis of a possible revision.

Imagine an island which will support 10,000 sheep. As long as there are 9,999 sheep or fewer it is in everyone’s interest to increase numbers, but at 10,000 or more the interests of each individual shepherd and the community as a whole are suddenly, diametrically opposed. But shepherds continue to increase their flocks because that was always successful. The island is over-grazed, and the society collapses into warfare, and worse.

Garrett Hardin must have been unaware of the history of Rapanui (Easter Island), or he would have quoted it in ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’. 1 I have paraphrased his classic essay, but what actually happened was that around AD 900 a Polynesian family arrived on a lush sub-tropical island smaller than the Isle of Wight (or Martha’s Vineyard). By 1500 there were at least 7,000, and possibly many more, but the trees used for fishing canoes, statue transport and which supported soil fertility were fast disappearing. Weapons first appeared then, followed shortly after by human bones instead of fish in rubbish heaps. On Easter Sunday 1722 a Dutch ship discovered 3,000 malnourished inhabitants on a barren island.2

Professor Jared Diamond offers evidence that similar self-destructive behaviour seems to have been typical of many, perhaps all human groups as they colonized new territories3. Garrett Hardin supplies a part of the explanation, but I believe a crucial part of the answer lies in their growth based cultural patterns. According to a television documentary presented by Dr. Alice Roberts, the entire human population outside Africa is descended from a single family group similar in size to the one which colonized Rapanui. That group (source of the Adam and Eve story?) crossed the southern tip of the Red Sea 70,000 years ago. Ever since then human groups have been expanding. The generally overlooked significance of that is that each and every human group outside Africa developed a culture suited to expansion.

Expansion must sooner or later meet limits. But instead of the foresight with which humans are credited leading to rational preparation for this foreseeable eventuality, a culture which has evolved to take maximum advantage of the potential to expand will normally be individualistic, and highly competitive. As competition for ever scarcer resources becomes intense, the reaction is not co-operation or restraint, but aggression, and then warfare. The first to reduce their demands on the environment do nothing to save it, they merely put them selves at a disadvantage. A globalised world is now on a similar course for exactly the same reasons, and this may be the first time that resource limits, or the effects of our waste products, especially CO2 are playing a part globally. Unlike climate change, on Rapanui there could be no scepticism on either the cause or consequence of felling all the trees. Yet with only 11 clans, they could not reach agreement to change their behaviour before the Trgedy of the Commons catastrophe.

Many see Capitalism (or Neoliberalism, the underlying philosophy) as the main problem. Capitalism has produced the modern world (not evenly shared), but as from now it poses a serious threat to the ecosphere – the global environment on which we all depend. But I think that attacking it will fail, for two reasons: capitalism is robust, and will successfully resist efforts to destroy it until it is too late, and it is a symptom rather than a cause. Similarly bankers have little regard for anything beyond their own short term enrichment. But again, bankers are symptoms. Rapanui destroyed itself although it had neither Capitalism nor bankers.

However, even if the ‘Tragedy’ is the norm, most societies recovered. Even on Rapanui, by the time Captain Cook converses with the islanders in 1774, the descendants of the survivors were beginning to evolve a sustainable way of life within the meagre resources remaining4. In contrast to Rapanui, the Siane, a tribe in New Guinea, had a culture which distinguished between necessities, which were shared unconditionally, and luxuries which could be traded in a kind of ‘free market’, so that everyone had an identity of interest when dealing with ecological limits.5 Despite their stone age technology and resources, the Siane perceived themselves to have a comfortable margin to spare above necessities. The reason so-called ‘primitive’ tribes did not develop advanced technology was not necessarily because they were less intelligent than Europeans, but because they did not need to.

But if Professor Diamond is right, the ancestors of the Siane must have gone through at least one ‘Tragedy’, and possibly more. But they had arrived at their present home, with strict physical limits, several millennia ago, whereas it was Rapanui’s first experience of dealing with resource constraints. Some use the successful management of existing commons6 to dispute the ‘Tragedy’ thesis, but this misses the point just made about encountering limits for the first time. But if the inertia of a growth-based culture was irresistible on Easter Island, how much more so is it globally? Agreements to limit activity require unanimity or effective control. Even the more obvious Green policies to save the ecosphere, recycling, public transport, renewable energy, reducing air travel, more efficient engines etc. etc. amount to cooling a fire by putting logs on it if used to prolong the mind set which doomed the Easter Islanders. As with them, our competitive culture is more likely to degenerate into aggression, warfare, and at worst genocide7.

If humankind is truly intelligent, then it should be possible for the world community to adopt a strategy for managing the global commons without first going through the ‘Tragedy’. We do not have to return to the Siane way of life, but we could adopt their strategy for sharing wealth. The key requirement is ‘an identity of interest when dealing with ecological limits’5. This leads most to think of socialism, but I believe something closer to the strategy which enabled the Siane to live sustainably, – share necessities, have whatever rules you like for anything else - will have a better chance of being adopted.

The central problem is that if we are to limit economic activity (or population), everyone must feel secure. An unconditional Basic Income (UBI) would be a natural form for the ’Siane’ strategy to take in a developed monetised western state, as a catalyst for the more obvious measures. At first it would be a thought experiment to get people world wide used to the idea.

Every man, woman and child will receive a weekly sum sufficient to cover food, fuel, clothing and accommodation. The UBI will be tax free, paid to individuals and unconditional. Everyone will keep it, working or not, or whether they need it or not. It will replace all existing social security benefits and tax allowances for the able bodied. It will be revenue neutral because it will be paid for out of taxation notably a Land Value Tax13. Resource taxes including carbon could play a part initially, but taxes to change behaviour cannot also raise revenue. Most of those on higher incomes will pay more in tax than the CI is worth to them.

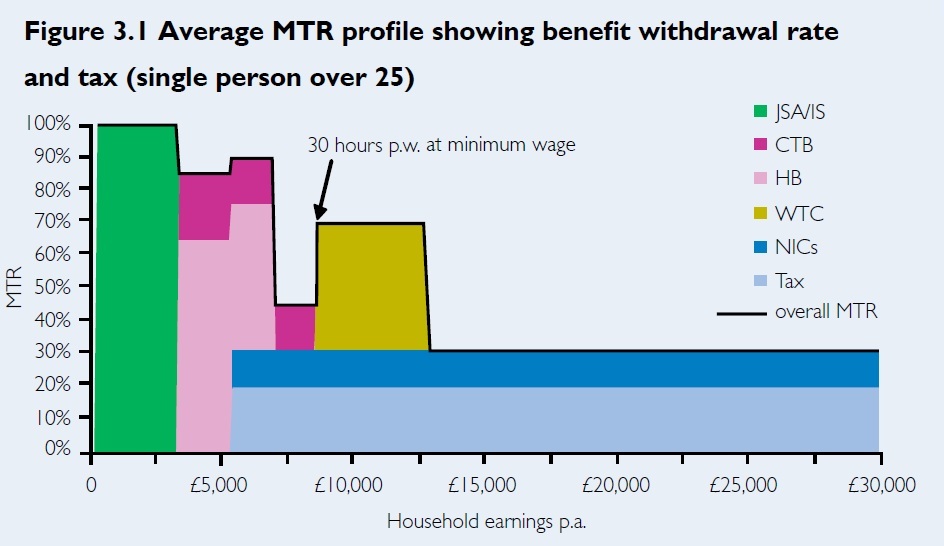

Crucially the UBI abolishes means testing. So far as low paid recipients are concerned, means testing amounts to a massive tax on their earnings. Actually everyone who does not receive means tested benefits pays this disguised tax on the first part of their income, but that is irrelevant for all but the lowest paid. This unorthodox view of the poverty trap is corroborated by a surprising source – Dynamic Benefits8, a policy report in a series edited by Ian Duncan Smith, later Minister for Work and Pensions in the UK coalition government, whilst he was still in opposition. The graph on page 88, reproduced at the top of this page, shows benefit withdrawal rates as if they were taxes, showing high tax-equivalent withdrawal rates on those losing means tested benefits. Dynamic Benefits explicitly admits that withdrawal of benefits is exactly the same as a tax so far as the person losing a benefit is concerned. Marginal tax rates vary between 100% and 70% on incomes from zero to £11,000 per annum, falling to 30% above that figure, eventually rising to 50% on very high incomes. Those who avoid entering the labour market are not ‘scroungers’ but are acting rationally.

The UBI merely shifts this real but hidden tax burden on to the shoulders of the better off. If critics object that the UBI means workers paying for shirkers, this has been so ever since means testing was introduced in England in 1603, but the workers who pay are those who narrowly fail to qualify for benefits, as the last paragraph explains. On the contrary, although the UBI does allow people not to work, it re-instates a work incentive. The point to keep clearly in mind is that

The UBI is simply an application of the ‘Siane’ strategy to a monetized world.

A communal approach to wealth sharing is indispensable to the primary purpose of an ecological identity of interest. This entails drastic redistribution, but a UBI is not as socialist as it seems. Market forces cease to be oppressive when individuals are guaranteed security. The UBI allows the better off, including entrepreneurs large and small, to keep some of their differentials. This crucial widening of potential support is more than a compromise between old enemies.

A minimum wage (MW), becomes unnecessary,and would prevent potential jobs from existing (a Living Wage even more so). Studies showing that a MW does not destroy jobs may be valid in in an expanding economy, but this cannot be true in a steady state economy. The ecological footprints of most of the world, and Britain in particular are already too large.

These facts are unpalatable to those who welcome the redistributive effect of a UBI. Similarly, notions of personal responsibility for one’s actions, unfair in a patently unjust society, will become important when security is guaranteed. The UBI must not encourage large families, as a growing population would not be consistent with sustainability. I would envisage a generous CI for a first child,9 an adequate UBI for a second child, but tapering amounts for subsequent children. Responsibility for childrens’ welfare will rest with the parents. In the modern context this scheme might look ‘right wing’, yet prior to 1911 it would have seemed radically socialist in the extreme.

It cannot be proved in advance, but if tied to a climate breakdown agenda, and ‘eco-footprint’ taxation, I predict that the UBI will tend to reduce economic activity. Bear in mind that Extinction Rebellion (XR) predicts an economic collapse if business as usual continues. There have been suggestions that democracy may have to be sacrificed if the planet is to be saved for human habitation10 . because anything other than growth has always caused hardship. The UBI makes downsizing thinkable

Old tribal attitudes still hamper rapprochement. Until those from both sides shift from a ‘growth’ to a sustainability paradigm realize that they now have more in common with their old enemies than their old unreconstructed friends, the Tragedy will proceed apace.

Green philosophy starts from the proposition that the ecosphere – the space within which life is possible – is a thin shell around a little ball. Some believe a technical solution will always be found to any problems. Their confidence seems justified because we have repeatedly won this gamble in the past, though not always without a heavy cost to some sections of humanity. But how will we recognize when the gamble does become foolhardy, and how will our competitive culture respond? Innovations may well make further expansion possible, but clinging to this hope is dangerous. As mentioned, even ‘Green’ measures are dangerous if used to avoid challenging the assumption of perpetual growth. We must get away from a dependence on growth. The normal expectation must be a steady state economy.

A steady state economy will look like a recession in terms of conventional economics, but it may be the norm at least from time to time. However, with the UBI continually recycling enough wealth for basic needs from the rich back to the rest, (the way the Siane lived comfortably within their means) this could be contemplated without the fear and insecurity which recessions must always cause in a growth economy.

Clearly such a Manifesto would be generally unpopular, but by 1974 I had established in election campaigns (for what later became the Green Party), that 10% of the public, even then, would take this uncompromising approach seriously. If a significant portion of that group could be persuaded to vote for such a party it would receive enough publicity for the wider public to consider the issues. The Party would become a ‘real’ party as more people were recruited as a result. I am not criticising the Green Party for choosing a more realistic strategy – building up from local grassroots groups – merely commenting that a need which I perceived was not met. Most people think the economy is more important than the environment. I believe the economy depends on the environment.

There are places in the world where some form of UBI is already in operation. One, a true uncompromising Basic Income has been tried in a small Namibian village by a coalition of German aid organizations11. The other strictly speaking is not a UBI – the Alaska Permanent Dividend Fund12, but it has features in common which allow us to draw some important and surprising conclusions.

In preparation for the oil coming on stream, the Alaska Permanent Fund – no mention of a dividend at first – was set up in 1976. It was a recognition that oil was a temporary bonanza, and the revenues ought to be invested in something more permanent. The use to which the fund should be put could be decided later. The first dividends were paid in 1982. The rationale seems close to Social Credit as advocated by C. H. Douglas over a century ago. All citizens of a state should be treated as though they were shareholders in that state as a business enterprise. The Permanent Fund is a relatively small portion of Alaska’s oil revenues, around 10% of the total. It must be invested in income producing assets, and only earnings, not the principal, can be spent. The Alaska PDF resembles a UBI in that every citizen (including children) who is and intends to remain a resident receives the same amount regardless of circumstances. The annual dividend paid in October 2011 was $1,174. The fact that the entire population has an interest in protecting the capital ensures that the PDF as a policy is theoretically secure.

The ‘Green’ purpose of the UBI is to combine equity and sustainability. The Alaska Permanent Dividend Fund has neither as its raison d’être. But among the more salient effects of the PDF is that the distribution of income in Alaska is one of the most equitable in the entire United States!11. This is despite overwhelming support for the Republican Party, with scant sympathy for egalitarian or social justice arguments. On the other hand, a ‘right wing’ effect of which I approve may also have occurred. The average real wage in Alaska has fallen slightly12, raising the possibility that higher incomes from the dividend are being partially offset by lower real wage rates. This would facilitate the creation of eco-friendly jobs.

Possibly relevant to the above mentioned odd state of affairs is the curious phenomenon of the Alaska Green Party. Given the general tenor of politics in Alaska, some might not expect it to be natural territory for a Green Party. By and large green parties are ‘left of centre’. Yet their electoral record includes some surprising results, of which the highlight was in the 2000 Presidential election, when they polled 10% – a much higher percentage than Greens anywhere else in the USA. That the Alaskan establishment is seriously rattled by the Green Party is shown by the fact that the state government passed a statute re-defining the meaning of ‘political party’. In 2007 this was upheld by the state courts as excluding the Green Party from the electoral process.

I am not surprised by the Alaska Green Party’s success. Green activists tend generally to be passionate about social justice, but Green voters are more likely to be the well-off who already have the sense of security a UBI will give everyone. In Britain up to and including the 1989 European elections Green votes were highest wherever the Conservative votes were highest. In 2000 the Alaska Permanent Fund was big enough (just short of $2,000) to extend that all important feeling of security to all citizens. It could give everyone that sense of ‘identity of interest when faced with ecological problems’, even though that was not its purpose.

The Alaska Permanent Fund may have even more far-reaching effects. A conference at the University of Alaska-Anchorage in April 2011 discussed ways in which the ‘Alaska Model’ could be applied elsewhere13. Resource-poor Vermont was used as an example. By applying the Alaska model to resources as diverse as forestry, groundwater, surface water, the broadcast spectrum, and so on, one contributor to the conference, estimated that Vermont could pay a dividend of at least $1,972. Another contributor combined this principle with the cap-and-dividend and tax-and-dividend strategies which have been proposed to address global warming. He estimates that a USA wide programme could produce a dividend of $678 per person. According to Karl Widerquist12, Iraq (with oil) and Mongolia (without) are seriously discussing this idea, and Iran was already phasing in a resource dividend which could turn out to be larger per capita than the PDF.

Although the conference was focussed primarily on social justice issues, none of these observation militate against the use of resource dividends as a source of revenue for the UBI, with the objective of sustainability.

The Tragedy of the Commons dictates that any measures to bring about sustainability will be ineffective as long as anyone can act independently. Sustainability in one country will not work, hence the need for a ‘thought experiment’ at first. So how do we bring the USA, China and all the others who are industrializing into a steady state consensus? There is an admittedly conjectural possibility bound up with the ‘Siane’ strategy. The trick is to reduce consumption internally whilst maintaining the ability to supply the unabated demands of others. China’s advantage relies on the fact that her workforce still has lower expectations than ours. If the UBI has the hoped for effect of reducing consumerism internally, however slightly, Britain would temporarily find itself in a stronger trading position! The minimum wage would hamper this possibility. This advantage is not the final object of the exercise, but it would prompt others to adopt the UBI with the same internal effect. That would allow the first rays of hope for effective international agreement. Rather than smashing capitalism, a better way to stop Earth-threatening expansion is for consumers – world wide – to stop feeding the beast: just reduce consumption.

To share necessities unconditionally, but to have whatever rules you like, subject only to their sustainability for anything else, is a strategy which needs to be adopted as between nations internationally, as well as between individuals within each nation. ‘Contraction and Convergence’ is one proposal which begins this process:

A policy in which all nations seek to reduce their levels of green house gas emissions, and converge levels towards a point where all citizens of the world are entitled to emit equal amounts of pollutants.14

Viewed from the perspective of finite resources, conventional ‘wisdom’ that prosperity depends on everyone buying as much as possible, and certainly more than ever before seems fatuous. But there are legitimate concerns to be addressed. For example, if goods are to be made to last, manufacturing will be decimated. But the UBI will not just cushion the worst effects, it will ensure that a certain level of economic activity always takes place. .As long as the resources are there, any activity which is sustainable can happen.

Even ignoring the need for sustainability, there is only one reason why rich bankers are on a more favourable tax regime than those defined as almost in need and that is because it is easier for the bankers to take their wealth elsewhere. But according to Martin Wolf of the Financial times, correcting this is politically impossible because the tax rate would probably have to be at least 60%15. Note that this is tantamount to an admission that those losing means tested benefits are already paying more. According to the Alaskan sources this should be alleviated by resource dividends, but in Britain perhaps these have already been given away too cheaply. Mr. Wolf is of course correct on conventional assumptions, including a resumption of growth, but not if civil unrest happens first.

The serious mistakes which led to the 2007 Eurozone debt crisis were all part and parcel of the growth economy, but as on Easter Island, a fresh start was made. If the UBI principle had been in people’s minds before the current economic downturn, the transition to a steady state economy could have seemed a natural outcome, in place of the fear and insecurity which has hitherto been associated with recessions. It will ensure that a basic minimum level of economic activity will always take place. The experts appear to be close to admitting that there are no answers within the ‘growth’ paradigm, yet they cannot think outside it.

The 1972 MIT Report Limits to Growth outlined the danger taken up by Extinction rebellion in 2018. I have tried to explain here why this enormous can has been kicked down the road for 46 years. But I must close with a caveat. The UBI is extremely dangerous. If associated with the Silicon Valley artificial intelligence agenda, it could generate economic growth and drive us even faster to the ecological cliff edge. It must be tied firmly to ecological limits.

Email clive.lord83@gmail.com Revised October 2019, from the hard copy published May 2011

References and notes to the original hard copy

1 Hardin, Garrett (1968) ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’ Science 162 (1968) pp1243-48

2 Diamond, Jared (2005) Collapse: how Societies choose to fail or survive Penguin/Allen Lane

3 Diamond, Jared (1991) The Rise and Fall of the Third Chimpanzee Vintage UK Random House

4 According to a Horizon documentary on BBC1 on 9th January 2003, strategies to live within their depleted environment had begun to emerge on Easter Island in 1774.

5 Wilkinson, Richard G. (1973) Poverty and Progress Methuen, London p48

6 Ostrom Elinor Governing the Commons (1990): The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action Cambridge University Press Shiva, Vananda (1989) Staying Alive: Women Ecology and Development Zed Books London. These sources do not directly refer to the ‘Tragedy’, but have been used as evidence against it

7 In The Rise and Fall of the Third Chimpanzee Professor Diamond identifies 37 instances of genocide between 1492 and 1990. There have been three since.

8 Dynamic Benefits: Towards Welfare that Works (2009) Economic Dependency Working Group, of the Centre for Social Justice 9 Westminster Palace Gardens, Artillery Row London SW1P 1RL www.centreforsocialjustice.org.uk

9 There will have to be a definition of ‘family’ which I do not address here

10 Ophuls, W, Ecology and the Politics of Scarcity 1977 San Francisco: Freeman; Hardin, G The Limits to Altruism 1977 Indianapolis: Indiana University Press; Heilbroner R, An Inquiry into the Human Prospect 1980 (2nd Ed) New York: Norton. The idea was discussed on BBC Radio 4 in 2010.

11 Der Spiegel 24th August 2009 www.spiegel.de/international/world/0,1518,642310,00html

12 For a detailed account of the Alaska Permanent Dividend Fund, see The Alaska Permanent Fund Dividend: An Experiment in Wealth Distribution A paper presented to the 9th International BIEN Congress Geneva, September 12th-14th 2002 by Scott Goldsmith, Professor of Economics, Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of Alaska Anchorage, 3211 Providence Drive, Anchorage, Alaska 99508 USA, Phone: 907-786-7720,Fax: 907-786-7739. http://www.basicincome.org/bien/pdf/2002Goldsmith.pdf

13 Alaska Permanent Fund Weblog posted by Karl Widerquiston June 6, 2011 http://usbig.net/alaskablog/author/karl/widerquist

14 Early Day Motion 538, placed before Parliament on 18.01.05

15 Email exchanges, whilst asking for permission to quote Martin Wolf in my book.